Prometheus Query Language - Prometheus Definitive Guide Part II

In the previous post, we covered monitoring basics, including Prometheus, metrics, and its most common use cases. If you’re just starting with Prometheus, I’d highly recommend reading the first part of the ‘Prometheus Definitive Guide’ series. In this blog post, we will focus on how to query Prometheus data. First, we will look into how to query the time series data with PromQL and its terms and try to apply its concepts to query the various metrics available within Prometheus. Let’s get started!

What is Prometheus Query Language (PromQL)?

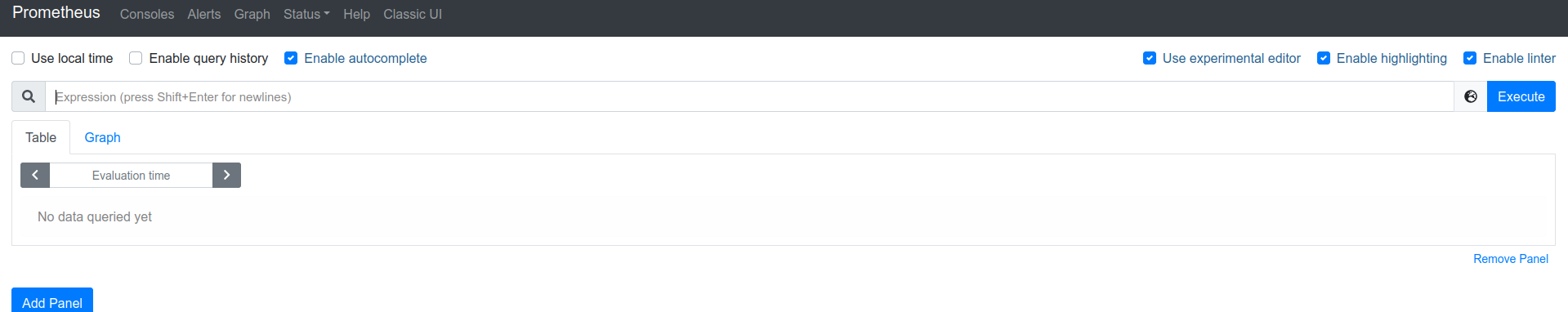

PromQL is a DSL (domain-specific-language) that enables users to do aggregations, analysis, and arithmetic operations on metric data stored in the Prometheus’ database. It consists of various functions and operators to construct the query. Each query of PromQL is called an ‘expression’. The expression browser provides the interface to run these expressions.

Image credit :Robust Perception

Image credit :Robust Perception

Data Types of Prometheus Expressions

Each PromQL expression can result in either of the following data types:

-

Scalar: The expressions resulting in a single constant numeric floating number is scalar.

-

String: The expressions whose output is a string literal is a part of this category. It is currently unused in Prometheus.

-

Vectors: Vectors are a set of time series. They include an extra dimension as compared to Scalar or string, i.e., Time. Any vector in Prometheus must have the following two components - value and corresponding time stamps. Vectors in Prometheus can be distinguished into two categories:

- Instant Vectors: These vectors have a single value corresponding to each timestamp in the time series.

- Range Vectors: These vectors have a list of values corresponding to each timestamp in the time series.

What are Selectors in Prometheus?

Selectors help users to narrow down the results of an expression. For example, prometheus_http_requests_total{handler="/alerts"} is a selector. Which will result in an all time-series having the metric name prometheus_http_request_total and label handler with value /alerts.

The handler="/alerts" is a matcher, and we can add more than one matcher in our expression. You can use the equal to (=), not equal to (!=), matching regular expression (=~), and not matching regular expression (!~) inside a matcher. You could find more about selectors here.

What are Operators in Prometheus?

Operators are used to modifying the resultant vector or scalar quantities of an expression. Operators are of the following types:

- Arithmetic Binary Operators

- Comparison Binary Operators

- Logical Binary Operators

- Aggregation Operators

Before performing any operation on the vectors, Prometheus expressions are used to find a matching pair of elements in the right-hand vector for each element in the left-hand vector. This procedure is called vector matching. It usually consists of two types:

a. One to One vector matching

This method tries to find all unique pairs of elements from each vector. Samples are selected or dropped from the result vector based on “ignoring” and “on” keywords.

The format for the query is like:

<vector> <operator> ignoring <labels> <vector 2>

<vector> <operator> on <labels> <vector 2>

b. Many to one / One to many vector matching

Many to one or one to many can exist when many labels match a single entry in either vector. In this matching type, samples are selected using keywords like “group_left” or “group_right”.

The format for the query is like:

<vector expr> <bin-op> ignoring(<label list>) group_left(<label list>) <vector expr>

<vector expr> <bin-op> on(<label list>) group_right(<label list>) <vector expr>

You can find more information about vectors here. We will be using some of these operators later in our example.

Functions

Functions are something which are pre-defined pieces of code. Each piece of code provides specific functionality.

They can be used for several different reasons, like changing the types of scalar to vector or vector to a scalar. Another use case is to perform mathematical operations like logarithmic of the resultant vectors. We will also talk about the use of the rate function on the counter metrics later in this post. Each function has a different set of parameters..

Basic Querying Examples

In this section, we will look at various query expressions applied to all types of metrics. We recommend you to try these expressions out on Robust Perception’s demo instance, as you go through them.

Gauge

The value of gauge metrics can increase or decrease. We, therefore, use aggregate operators like sum, average, minimum, or maximum.

For example:

To calculate the total number of available bytes combining all the partitions, we can run the following query.

sum by(instance)(node_filesystem_avail_bytes)

The by is an aggregation operator. In this particular case, this query sums all the metrics where the value of instance label is same. If there are 2 different values of instance, then there would be two results. The result has only instance label as a side effect. Input:

node_filesystem_avail_bytes{device="/dev/vda1", instance="demo:9100"} | 1234

node_filesystem_avail_bytes{device="/dev/vda15", instance="demo:9100"} | 4567

node_filesystem_avail_bytes{device="/dev/vda1", instance="demo2:9100"} | 1234

Output:

{instance="demo:9100"} | 5801

{instance="demo2:9100"} | 1234

Or, we can aggregate the metric with maximum or minimum to find the largest or smallest partition.

max without(device, fstype, mountpoint)(node_filesystem_size_bytes)

min without(device, fstype, mountpoint)(node_filesystem_size_bytes)

Similar to by, without is also an aggregation operator. The labels specified using without are skipped while doing the aggregation; it is opposite of what by does. The result does not have the given labels as a side effect.

Counter

As we know that metrics of the counter type are always incremental, our interest lies in how fast this metric value increases or decreases.

For example, let’s take the metric prometheus_http_requests_total, which counts the total number of HTTP requests. We can extract the rate of growth of requests from this by using the rate function (requests per second).

rate(prometheus_http_requests_total[24h])

This gives us the rate of increase or decrease of HTTP requests per second averaged over the past 24 hours. The output is a gauge metric; hence we can use aggregation operators like sum, max, or min. The following query will produce the total HTTP request per second averaged over the past 24 hours.

sum without(code,handler)(rate(prometheus_http_requests_total[24h]))

Summary

A summary metric exposes three types of metrics with suffix _bucket, _sum, and _count, respectively. The _bucket metric generates observations under a specified limit of the metric. All of these sub-metrics are of type counters. We can use them like any individual counter-type metric.

For example, let’s take the metric prometheus_http_response_size_bytes, which is a summary. If we want to calculate the rate of the total number of HTTP request per second, we would have to run the following query:

sum without(handler)(rate(prometheus_http_response_size_bytes_count[24h]))

To calculate the number of bytes returned by Prometheus, we can apply the same logic as above.

sum without(handler)(rate(prometheus_http_response_size_bytes_sum[24h]))

To calculate the average response size, we need to divide the above-stated queries.

sum without(handler)(rate(prometheus_http_response_size_bytes_sum[24h]))

/

sum without(handler)(rate(prometheus_http_response_size_bytes_count[24h]))

Histogram

The Histogram metric can calculate a more accurate quantile than the summary; therefore, it is often used over a summary. A histogram metric also exposes three types of metrics with suffix _bucket, _sum, and _count.

For example, let’s take a metric prometheus_tsdb_compaction_duration_seconds, which counts how many seconds it takes to do a compaction operation on the current data block to save it in the background as a more significant chunk of data.

Each metric having the _bucket suffix has a limit defined in its labels, like {le=5} and its value shows how many samples satisfy this condition i.e. how many request take less than 5 seconds. The metric with _bucket suffix is of type counter. Hence we will need a rate function on this before proceeding further on quantiles.

For calculating the quantile, we need a function histogram_quantile which takes two inputs, the quantile percentage and the time series for _bucket metric.

histogram_quantile(0.99,rate(prometheus_tsdb_compaction_duration_seconds_bucket[1w]))

The query mentioned above gives me a result of 1.93 which means that 99 percent of our requests have taken less than 1.93 seconds to complete the compaction. We can check the _count suffix for this metric like this;

prometheus_tsdb_compaction_duration_seconds_count

We can also extract how many requests in total have taken more than 1.93 seconds. To do so, we will take 1 percent of the value given by prometheus_tsdb_compaction_duration_seconds_count. In my case it was 133, so 1 percent would be equal to 1.33. Since requests are integers let’s round off 1.33 to 2. Now we can say at most 2 requests took more than 1.93 seconds.

Conclusion

Let’s do a quick recap before concluding this post. We discussed PromQL and explored its various components like Selectors, Operators, and Functions. All of these components are not separable, and often each of these appear in a single query. We also looked at some real-life queries which can be used at the early stages while learning and exploring PromQL.

We hope you found PromQL post informative and engaging. For more posts like this one, subscribe to our weekly newsletter. You can also follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Looking for help with observability stack implementation and consulting? do check out how we’re helping startups & enterprises as an observability consulting services provider.

References

- Official Prometheus documentation

- Brazil B.(2018) Prometheus: Up & Running. O’Reilly

- Official Prometheus blog

- Robust Perception demo installation

- Prometheus monitoring consulting and enterprise support capabilities

Stay updated with latest in AI and Cloud Native tech

We hate 😖 spam as much as you do! You're in a safe company.

Only delivering solid AI & cloud native content.